Having heard that Cork is named after the Irish word for “marsh”, and knowing Paul is based there, I had a fair idea what this poem would be about when I saw the title. The way the poet went about it, though, surprised me. I’ve come across pieces from the point of view of an object or an animal, but never, that I can remember, a city.

And what kind of person would you expect such a manifestation of Cork to be? (No jokes, please. There’s no “Cork is great!” here.) It’s revealed to have a somewhat philosophical voice, weary with experience, an observer of change. The “mane of reed” becomes pylons and beggars over time.

Writing about place is a standard practice in poetry, but it usually involves the poet divulging details of his/her relationship with that place, entwined with memories and emotions. Thinking about it that way, what Paul Casey does here is quite a selfless act, an act of giving voice to the city of Cork. And why not give back to that from which we take so much? This is a poem of generosity and imagination. Think about it the next time you’re strolling the streets of Cork.

Marsh

I was all bog and bits of islands

My bird-heavy mane of reed

a river of lyrical russet

A Celtic hunter slowing his currach

to the heartbeat of a wayward doe

I grew wooden bridges and jetties

Ramparts and Towers cupped huts

and dirt roads. Smoke rose nightly

from the duels of swords and harps

I sank heavier with merchants and markets

Cobblestones, cannons kept alehouses then

Top hats and summer umbrellas tilted

to soldiers and carriages. Oil street

lamps lit stocks and paupers

Men and metal stitched me whole

Now I sleep with buses and pipes

Pylons and beggars reflected thrice in glass

Mobile phones and mini-skirts flirt my name

while coffee-shop buskers point tourists to pavement art

What will I not endure?

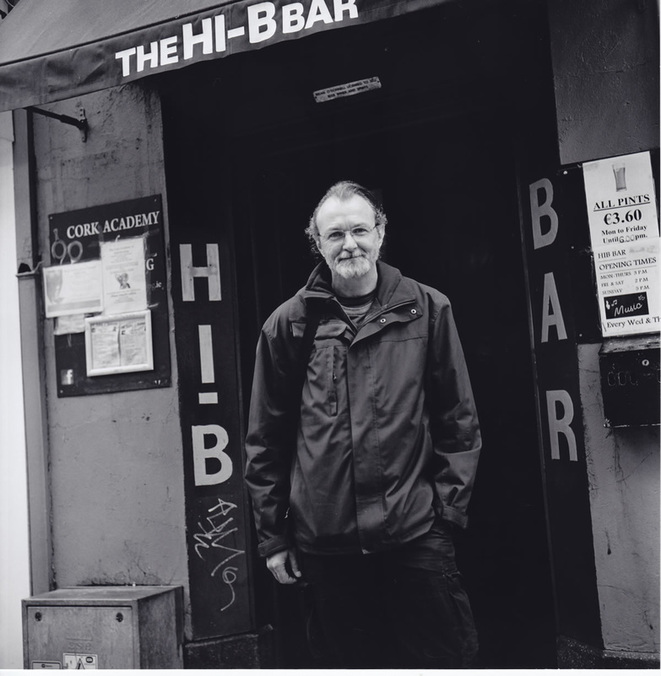

I’ve been writing poetry for about 25 years now, and seriously for the past 15. I also have a filmmaking background, and consequently a special affinity for poetry films. My second collection Virtual Tides appeared from Salmon Poetry in early 2016. My début is Home more or less (Salmon, 2012). A chapbook, It’s Not all Bad, appeared from the Heaventree Press in 2009. I also edit the annual Unfinished Book of Poetry (transition year writing), work with the elderly through poetry appreciation during the Bealtaine festival and am the founder/director of Ó Bhéal in Cork, at www.obheal.ie.

Interview

Writing from the point of view of a non-human speaker, such as an object or place, can be a tricky thing to pull off, I'd imagine. What are the most interesting and challenging aspects of this approach?

I think one is faced with very specific challenges when pursuing an anthropomorphic approach to a poem. It's one I teach with, to help develop empathy (within the craft). Speaking from the point of view of an object often reveals more to the writer about themselves than about the object (which may be exactly what the poem wants). But aside from the potentially distressing notion of identifying with the non-sentient world, I think the poem's symbolic foundations need to be much stronger and more complex than usual - for it to succeed well. It'll work better with some objects than others, depending mostly on the writer's personality, tastes and experience. I identify more with the spirit of a salmon than a dolphin. More with a cheetah than a lion. A three-dimensional spiral, than a sphere. Which doesn't mean I won't attempt the voice of a dolphin or lion or ball to represent someone or some place else. I can still imagine what it is to be a lion, and I'd prefer to be in a cage with it than sit through the torture of a Strasberg method acting session, trying to 'be the teapot'. Or writing from the perpective of a tennis ball, without any strong sense of symbolic connection or purpose.

As I've lived mostly in cities, I find them much easier to identify with than towns. People often personify cities in everyday speech, so it wasn't a strange notion. 'Prague welcomed us with open arms', 'Paris can be cruel', etc. I identify with Cork much more so, of course, as I'm from here. And I love the idea of a great silent witness-spirit, benevolent or otherwise. Yet, a tree in a forest or laneway may be no less significant, in terms of symbolic potential. In fact, I usually find the simpler the image the more effective the metaphor. But not always. Marsh is the enduring collective voice of Cork city, embodying the histories of its generations, since long before any humans. So in this sense it's also an environmental piece (another of my prevailing themes). I have often sought to describe the spirit of a city. The title poem in home more or less personifies Dublin, which 'talks in its sleep, softly''. I also love the idea of a passive, sagacious witness, persisting across the ages. Like the many lives of Fintan mac Bóchra. With a city like Cork and its palimpsest of exquisite stories, I found it easy to personify, to transmogrify into an underling of that wise gentle spirit of sparse words (time), so the complexity of the city could be rendered simple, or at the very least, less intimidating. The poem was one of those rare gifts - it came to me very, very quickly. But simply put after having said all that - I love history, I love Cork and I love poetry. It was a three-way made in heaven.

The theme of a town changing is more associated with songs, I think (eg. "The Town I Loved So Well", "The Rare Oul' Times"). Were you conscious of this, or did you feel that music influenced you here in any way?

Music is central to my poems. To me, without it there is simply no poem. As the renowned Lesego Rampolokeng once wrote, 'it all begins with sound'. I wasn't conscious of it though, no, not any more so than usual. Of course Cork is a city of music in its own right too, so I imagined harpists vying for patronage along its bustling streets, centuries ago.

By the end, it seems that this poem is a lament. Do you think poetry is particularly suited to lamenting?

I'd say “Marsh” is more of a praise poem than a lament, although there is a (necessary) strain of the latter, keening out from the string section. Loss and endurance are obviously not mutually exclusive within human experience. Still, to me they are inevitable, inseperable companions. I feel that poetry and song hold equal potential for the lament. Both are entirely suitable, sorrow being expressed most poignantly, I feel, via the human voice. Probably much more so than through any other art form.

The past features strongly in this poem. Could you tell us about how the past informs your writing in general?

I've always been magnetically lured by history and to the context and understanding it ultimately offers. I probably read more history than any other form of prose and I certainly watch more historical fiction than any other film genre (outside of poetry-films). So there's often an historical aspect at play, while overall my work is eclectic in content and can ignore history entirely.

Why do you write?

Often I haven't a clue why, sometimes for the craic, but I'd guess mostly for discovery and often for personal transformation. Sometimes its educational potential, or simply to celebrate. When it's hot I think of jumping into the sea, and do if I'm able. When I get itchy feet I go a-wandering. When I'm overly curious about something I think about teasing out its secrets, which often show me my own, and for that my hand reaches for a pen. It's the best way I know how to offer form to the unspoken. To the new. To my new.

If you had one piece of advice for a writer, what would it be?

Read and write. Read a poem every day from a known poet, then another from an unknown poet. You could make a rule: if the first poem you read leaves you disappointed or wanting, keep reading others until you find one that surprises you, or at least shows you something new. It can be as quick as making coffee and will filter straight into your neural database of what's possible. And write a poem every day too, no matter how short or ridiculous. Eventually you'll be equipped for a masterpiece. For when it arrives. It's up to the gods then.

(The video below is taken from Balcony TV. Paul gives a short interview, and reads both “Marsh” and other work)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed